The recession is the bogeyman of capitalism. Businesses and private households fear loss of prosperity and potentially existential impacts; the state faces economic and societal instability; and governments worry about their re-election prospects amid increasing citizen dissatisfaction. Everything is done to avoid or at least mitigate a recession.

However, the fear of recession displaces its quite meaningful role as part of the economic cycle from the consciousness of many people. The economic downturn compels companies to be resource-efficient in order to survive during times of low demand. Many companies fail and disappear from the market. Following the spirit of Schumpeterian creative destruction, this creates space for new companies and innovations, which in turn lay the foundation for growth and prosperity in the next economic cycle.

The current economic cycle began with the upswing after the great financial crisis in 2009. Since then, governments and central banks have been moderately successful in stifling potential recession risks with cheap central bank money and state subsidies, keeping the economy running.

However, this causes the entire economic cycle to remain in an unnatural prolonged boom phase for more than a decade, during which constructive market adjustments and innovations have largely been absent.

Yet, the more forcefully and extensively monetary and fiscal measures intervene in the economic cycle, the more painful the inevitably following recession will be. This increases the fear of recessions, which in turn leads to even more massive interventions.

This vicious cycle manifests with various symptoms, including high inflation, an increase in state subsidies and “too-big-to-fail” company bailouts, a growing societal gap between the rich and the poor, bubbles forming in asset classes, and the monopolization of companies.

The latter is due to the fact that large corporations particularly benefit from delaying the recession. Given the constant subsidized demand, they do not need to continually improve their products and processes and face minimal pressure to develop and implement innovations. In short, they need to invest less in securing their competitiveness and can dedicate more time to expanding their market power. In such a market environment, fewer and larger corporations increasingly dominate the market proceedings.

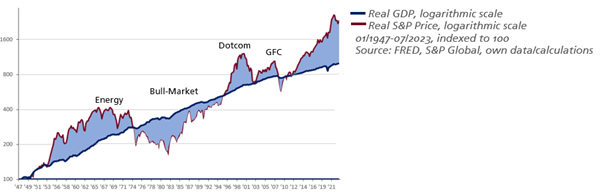

Monopolization and the formation of bubbles are also evident in excessive valuation levels of companies. This is illustrated by the above chart, which juxtaposes the development of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) against the capitalization of the S&P 500 Index for the United States since 1947.

In most cases, major crises have been preceded by stock market growth that was disproportionately strong compared to economic performance. However, never in history has the S&P 500 Index become so disconnected from the GDP as it is today. Just to return to GDP levels, the index would need to correct from its current level of around 4,500 points to about 1,900 points. It is likely to descend even further, especially if corporate valuations initially overshoot in the opposite direction when normalizing. Since market excesses are never worked off sideways (and GDP can hardly catch up), the return to normalcy is likely to be accompanied by rapid declines in stock prices.

In June, The Wall Street Journal published an analysis of economic cycles since 1889. Interestingly, the lead-up to the stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent “Great Depression” bear striking similarities to the current situation. From 1921 to 1929, there was a period of extremely low interest rates and cheap central bank money – the Fed increased the money supply by over 60% in eight years (2009-2023: 110%). This led to rapidly rising stock prices and rampant stock market euphoria. During that period, the Dow Jones Index increased by 500% (S&P 2009-2023: 300%).

Subsequently, the collapse in October 1929 marked the beginning of the most severe and prolonged global recession in history. While the unemployment rate in the United States was only 3.5% in mid-1929, it had already surpassed 25% just two years later, even higher in many other countries. The Dow Jones lost 90% of its value and took more than 15 years to recover. The worldwide economic and social upheavals led to massive geopolitical and political changes. In Germany, in combination with the preceding hyperinflation resulting from reparations payments under the Treaty of Versailles, the “Great Depression” laid the groundwork for the rise of the National Socialists and thus significantly contributed to the outbreak of World War II.

So, is today’s fear of a global recession justified, or does the phrase “This time is different” hold true after nearly 100 years?