Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell believes it’s time to retire the term “temporary inflation” and is compelled to undertake a monetary policy shift with the Fed. Among the leading global central banks only the ECB still adheres to the narrative that inflation would disappear on its own in 2022 . Is Mrs. Lagarde underestimating the dangers of inflation or is she unable to act in the wake of fiscal policy?

As early as 2010, at the beginning of the bond purchasing programs, warnings were issued about the loss of central bank independence and potential inflationary consequences due to monetary financing of the state. Since then, it has become clear that higher debt levels and an expansion of the money supply during economic crises do not necessarily lead to widespread price increases. However, the longer the cheap money drug remains available, the greater the risk. The favorable financing has made it easy for European governments to postpone the necessary but unpopular austerity measures, such as tax increases, to the next legislative periods.

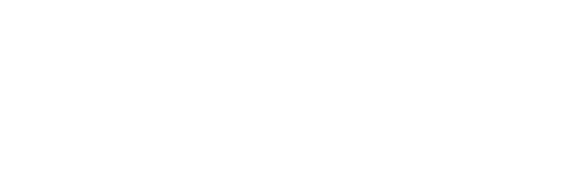

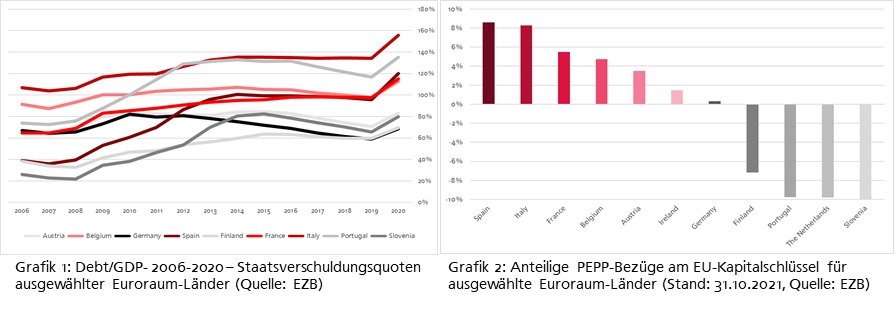

The development of European debt-to-GDP ratios since 2006 (Chart 1) shows the differences in fiscal discipline of selected member countries of the currency union. Only a few have taken consolidation measures to reduce the debt overload since then in accordance with the growth and stability pact. Others, on the other hand, have expanded their deficit and still rely on the indirect monetary financing by the ECB through its European bond purchase programs (Chart 2). Massive redistribution of wealth between the different European economies is one of the consequences.

The divergence of the currency and economic union has rather increased than decreased since the crisis of 2013-2014 and government debt has skyrocketed since the coronavirus aid funds. Neither the pandemic is over nor its long-term economic effects are in any way foreseeable. One of them is the sudden global inflation. In accordance with its primary mandate, the ECB must also consider taking monetary policy measures to ensure price stability. The necessary restrictive measures, ending the bond purchase programs and raising interest rates, are obvious. Both, however, are problematic.

Just the announcement of a reduction in the volume of bond purchases at the beginning of 2022 causes risk premiums for European government bonds to rise on the market. Italy, with the highest debt-to-GDP ratio of 184% (2020), is the most affected. Assuming very conservatively that risk premiums will climb back to the highest level of CDS spreads for Italy’s government bonds in the last five years (around 286 basis points), the cost of Italy’s new borrowing will increase by at least 2%. The annual interest expense already eats up around 10% of Italy’s government revenue.

At some point, additional interest rate hikes by the ECB are likely to make the pot overflow. Since fixed interest coupons of bonds held by a central banks become floating in terms of the ECBs profit and loss account, any change in the policy rate has an immediate effect on the entire ECB debt stock. Assuming an interest rate increase of 1%, about 25% of Italy’s total debt, which is held by the ECB, would be affected. An increase in interest rates would increase Italy’s interest burden from today’s 3.5% of GDP overnight to more than 4%. The interest expense relative to government revenues would increase by another 1-2%. Dynamic, self-reinforcing effects are not yet included. With an interest burden of about 15% of revenues, it becomes clear that restrictive monetary measures by the ECB would lead to the bankruptcy of Italy and some other member states in the near future. It is unlikely that the member states will have the political will to jointly rescue the over-indebted countries, including the third largest economy in Europe. The collapse of the currency union would then be unavoidable. It is expected that the ECB will do everything in its power to avoid this scenario and take high inflation rates into account in exchange for the survival of the euro. However, this path is at least equally dangerous. Inflation-related redistribution effects deepen social divides and promote conflicts, they lead to the radicalization of people and fuel anti-state counterviolence. The redistribution of creditors to debtors at the intergovernmental level reinforces the existing centrifugal forces in the EU and makes it vulnerable to populist sentiments. Ultimately, this alternative to the ECB (better: non-trade alternative) leads to the destabilization of the EU over the short or long term and will accelerate the dissolution processes within the political union. This will hardly survive the single currency, but political differences in the EU will be the trigger, not capital markets.

Faced with this choice, President Lagarde would rather sit out the situation for the time being, in the hope that inflation is only temporary.